| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

2.gif) |

Chroniques |

|

| |

|

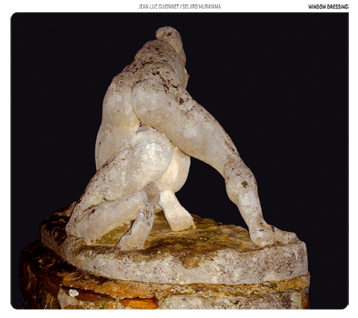

Seijiro Murayama est un subtil percussionniste japonais désormais confortablement installé – on ose l’espérer – en France depuis de nombreuses années et il a publié au cours de l’année 2011 deux enregistrements magnifiques et essentiels sur le label Potlatch dédié aux musiques improvisées et bien connu des amateurs du genre. Voici l’un de ces deux disques, Window Dressing, en duo avec l’altiste Jean-Luc Guionnet (encore tout récemment évoqué ici à propos de l’album Bird Dies de The Ames Room). Il ne faut absolument pas se fier à la photographie, d’ailleurs signée Jean-Luc Guionnet, servant d’illustration à ce disque délicat et exigent : si on pense y découvrir une scène de lutte assez âpre entre deux hommes, au contraire les quatre pièces de Window Dressing éradiquent d’emblée toute idée de violence physique voire même de confrontation. Le silence ou plutôt les silences sont placés au cœur d’un disque dont l’écoute ne nécessite qu’un seul petit effort, celui du recueillement.

Ainsi on n’entend que très rarement des notes sur Window Dressing, tout au plus y découvre-t-on des sons et encore ceux-ci sont loin de faire l’objet d’une quelconque construction apparente ou d’un réel agencement formel. Car tout se passe à l’échelle du ténu (et non pas tenu), du presque émis et donc de l’évènement imperceptiblement palpable et de la surprise lorsqu’un son ou une suite de sons dépassent la ligne de crête observée par tous les autres. Musique de l’effacement, de petits bruits et surtout musique abstraite, les dialogues micro-bruitistes de Jean-Luc Guionnet et de Seijiro Murayama ressemblent à ces vieilles maisons qui grincent sous le poids des ans, ces canalisations qui fuient, ces cornes de brume estompées par le brouillard d’un port baltique, ces toupies qui s’échouent sur le froid du carrelage, ces grincements de mécaniques invisibles mais omniprésentes ou ces bruits de pas qui s’effacent sur du gravier : une musique très urbaine car on aurait du mal à y retrouver une quelconque trace tangible de la nature terrestre mais en même temps une musique qui ne recourt pas prioritairement à l’électricité.

Sans directement évoquer quoi que ce soit de la nature en tant que telle, les quatre pièces de Window Dressing ont par contre un mode d’expression des plus naturels car les mécaniques détraquées mises en scène ici ne le sont que de manière impromptue, éphémère et accidentelle, des bribes de dialogues entre deux musiciens, comme si ceux-ci étaient plongé chacun de leur côté dans leurs propres pensées à propos d’un sujet commun et que, à chaque fois que leurs pensées se rejoindraient malgré eux, il en résultait cette force d’attraction ou ce cliquetis magnétique, en clair ce son ou ces sons que nous les auditeurs entendons, en dehors de toute signification rationnelle et préméditée. Window Dressing a ainsi tout de la rêverie.

La première pièce de Window Dressing est aussi la plus longue et a été enregistré pour une émission de radio slovène. Les trois suivantes ont été captées par Eric La Casa à l’aide d’un micro stéréo placé sur une perche : un enregistrement mobile et donc dynamique, jouant considérablement sur les sons. La dernière pièce ferait ainsi presque figure de musique électroacoustique tant les sons captés et donc diffusés semblent encore plus détachés des sources instrumentales qui les ont produits. On se plairait à assister à un concert déambulatoire du duo Seijiro Murayama - Jean-Luc Guionnet, avec les deux musiciens évoluant selon leurs désirs entre les personnes du public, tout doucement, leurs effleurements et leurs mouvements perturbants d’autant leur musique. Une vue de l’esprit, assurément.

Hazam Modoff l Heavy Mental l Mars 2012

C'est toujours un vrai plaisir de recevoir des nouvelles de Seijiro Murayama. D'abord, le garçon est aussi adorable que l'artiste est original. Ensuite, lesdites nouvelles sont le plus souvent musicales et grosses de promesses à tenir. Enfin, il est plutôt rassurant de constater qu'un type aussi radical dans sa démarche créatrice trouve encore, de nos jours, le moyen de publier deux albums aussi différents sur un seul et même label, en l'occurrence Potlatch.

Le premier, dans mon ordre personnel d'écoute, le met en présence de son vieil ami, le saxophoniste Jean-Luc Guionnet. Ensemble, ils ont déjà enregistré Le bruit du toit (2007, Xing Wu), puis Noite, face aux violon et violoncelle des Rodrigues, père et fils (2008, Creative Sources). Ils ont participé aux performances les plus troublantes et croisé les personnalités les plus insolites, susceptibles d'alimenter encore la douce folie de leur double univers : Mattin, Diego Chamy, Ray Brassier… En bref, leur couple n'est pas né du dernier concept à la mode et ne considère visiblement la viabilité de son existence que dans la pérennité de l'expérience, quel que soit le domaine de sa recherche.

Ainsi, dans ce Window Dressing que l'on sent enregistré les yeux dans les yeux, à l'affût du moindre signe d'intelligence, leur champ d'expérimentation se situe aux alentours de ce que l'on appelle, faute de mieux, le silence et qui n'est, en fait, qu'un temps plus ou moins long s'étendant entre deux manifestations sonores. Depuis Cage, puis les divers minimalistes ou réductionnistes qui se sont abrités sous les diverses appellations de New London, New Berlin ou New Garges-Lès-Gonesse, Silence, cette forme d'espace-temps indéfini est en effet devenue un sujet brûlant traité le plus souvent par la négative et le refus pur et simple du jeu. Or, là n'est pas le propos de nos deux improvisateurs, nettement plus investis dans la lutte pour l'expression que dans la fuite vers l'introspection !

C'est Jean-Luc qui, le premier, rompt une amorce de trente secondes en un slap autoritaire à peine annoncé par un mince filet de souffle cuivré. Le phénomène se répète plusieurs fois, à intervalles irréguliers, jusqu'à ce que Seiji prenne le relais avec un bref aller-retour des balais sur la caisse claire… En quelques sons échangés, le duo a défini le cadre de ses investigations : l'exploration de ce silence qui va bientôt se révéler une matière première à la richesse insoupçonnée dont il ne s'agira plus, désormais, que d'évaluer l'épaisseur, le relief et la densité, d'en saisir la texture et de le circonscrire au moyen d'accidents volontaires suffisamment précis pour en estimer la géographie. Le métal des balais tisse sur la peau une toile de fond intermittente au travers de laquelle on perçoit la respiration du souffleur, insiste, par son frottement, sur la régularité du non rythme soutenant l'ensemble ou interrompt brusquement la discussion par une frappe sèche comme un coup de trique. Le cuivre oscille entre le découpage d'un temps incertain, la tension de son propre souffle suspendu et l'éclat soudain de sa brillance maintenue quelque temps aux abords d'un expressionnisme hors de propos dont la proximité met à jour le danger constamment repoussé par le duo. Et ce ne sera bientôt plus qu'échanges libertaires, partage des rôles et vibration humaine. Que cela frotte, siffle, frappe, sonne, frôle ou se taise, la musique et son absence, uniques résonances d'une mise en attente permanente mais perpétuellement interrompue, vont circuler entre la seule caisse claire et le saxophone isolé selon les termes et les lois d'une architecture immédiate dont la fonction consiste à définir le vide séparant les bornes qui le déterminent.

Cet enregistrement rayonne, de l'ouverture à la coda, d'une intelligence révélée dans la mise en suspens constante de tous les éléments constitutifs d'une œuvre en construction. Comme si les murs, les portes et fenêtres et le toit d'un quelconque bâtiment flottaient dans l'air et ne pouvaient se poser qu'une fois les parties du tout réunies. Alors, ce fameux silence, matière première d'un album éblouissant, peut enfin submerger l'espace et le temps puisque l'écoute est achevée.

Joël Pagier l Improjazz l Janvier 2012

Deux homme nus. J’imagine des lutteurs ce la Grèce antique. L’un a les genoux à terre, l’autre s’arc-boute sur son corps. Trois cadrages différents servent de visuel à ce disque; trois cadrages qui permettent de se figurer l’essence de la statue, d’essayer de se la représenter à défaut de l’avoir, en trois dimensions, devant ses yeux. Ces trois cadrages, pris séparément, sont trois points-de-vue artistiques autonomes sur l’oeuvre d’un sculpteur anonyme.

J’y vois une belle métaphore de la relation musicien – preneur de son. Et nous avons justement là un disque ou l’on peut écouter deux cadrages ou tournages (comme dirait Michel Chion) différents sur un même duo d’improvisateurs.

Le premier tournage, assez classique dans son approche, a été réalisé par la radio nationale Slovène. Il nous permet d’approcher le caractère délicatement sensuel de la musique de Jean-Luc Guionnet et Seijiro Murayama. Un appel aux sens qui passe par ces délicats frottements de peaux, ce souffle discret, ces claquements de langue, cette approche pointilliste de la percussion. L’oreille de l’auditeur ne peut s’empêcher de faire travailler un imaginaire qui ramène à d’autres sens : vue, toucher. On a l’impression que cette musique est trop délicate pour que l’on puisse entrer en son coeur, et que les deux musiciens eux-mêmes tels des stalkers, n’osent pas s’aventurer au centre, gravitent autour d’un noyau duquel il serait dangereux de s’approcher.

La seconde partie vient, au contraire, nous démontrer que le cœur de cette musique peut être atteint, touché par l’oreille, et que les deux improvisateurs en sont bien le noyau d’où tout émane. Eric La Casa a réalisé ce tournage du duo à l’aide d’une perche. Une écoute au casque permet d’abolir la distance entre l’auditeur et les musiciens, tellement on se sent au cœur-même de la musique. Plus question de point-de-vue car on aboutit à une image absolue, une représentation unique, qu’aucun auditeur du duo en concert ne pourra approcher.

Window Dressing, au-delà de continuer à documenter la musique d’un des duos les plus passionnant de la scène improvisée actuelle, se présente comme une expérimentation discographique à part entière qui mérite grandement qu’on lui porte intérêt.

Freesilence's Blog l Octobre 2011

Window Dressing est le deuxième essai du duo Guionnet/Murayama (respectivement saxophone alto et percussions) après Le bruit du toit, paru en 2007. Sur le site de Jean-Luc Guionnet, nous pouvons lire à propos de la première forme du projet qu'il consistait avant tout en une improvisation in situ, la musique étant principalement déterminée par l'environnement dans lequel elle prend forme. Etant donné que Le bruit du toit fût enregistré en studio, il s'agissait dès lors de "faire un concert comme non-concert. A la recherche de l'absence" (Murayama), d'où une certaine forme d'austérité et de froideur d'après mon souvenir de ce disque. Mais pour Window Dressing, les données changent car les deux sessions qui composent ce disque furent enregistrées en live: la première à Ljubljana lors d'un concert organisé par Zavod Sploh, et destinée à une diffusion radiophonique, la seconde, saisie à la perche par Eric La Casa dans une bibliothèque parisienne.

Durant ces quatre pièces, la spontanéité semble régir la plupart des structures et des modes de jeux. Comme le notait Jean-Luc Guionnet en 2007 déjà, tout deux semblent autant réagir aux propriétés spatiales et acoustiques du lieu dans lequel ils jouent, à l'écoute et à l'attention du public, qu'aux techniques instrumentales et aux caractéristiques sonores adoptées par chacun. La tension résultant de la concentration et de l'attention à tous ces paramètres est palpable de bout en bout, au sein de la musique d'une part, mais également au sein de l'écoute de l'auditeur lui-même, pour qui une certaine forme d'attention assez singulière est requise. Attention au silence, attente de ce qui surgira potentiellement de chaque silence utilisé pour lui-même comme une matière sonore intentionnelle. Attente également de la forme toujours surprenante que prendra la forme de réponse à chaque intervention ainsi qu'à chaque non-intervention. Car le duo Guionnet/Murayama sait composer aussi bien avec la présence (sonore) de l'instrumentiste qu'avec l'absence (de son ou d'un instrumentiste).

Et c'est certainement ce dialogue entre la présence et l'absence qui forme la profondeur et les multiples contrastes de ces improvisations. Contrastes d'intensités qui vont du silence long et pesant aux notes criardes et stridentes de l'alto, en passant par des caisses claires doucement percutées de manière sporadique. De manière générale, tout paraît plutôt erratique, et la profondeur vient également des multiples modes de jeux utilisées au gré de principes intentionnels opaques: slaps, souffles, caisse claire sensiblement frottée par des balais, flatterzunge, pulsations énergiques et entêtantes (sur caisse claire toujours), longues notes tenues sans variation, ou avec, ou brutalement interrompues, de même que ces phrases percussives parfois trop sauvagement stoppées. Toutes ces techniques s'entremêlent sans jamais fusionner, car la musique de ce duo n'est pas seulement le fruit des musiciens, l'interaction se fait primordialement avec l'environnement (pas uniquement sonore cependant).

Window Dressing est un dialogue très surprenant entre deux musiciens d'une part, mais également entre les instrumentistes et le contexte environnant. Un dialogue basé sur une écoute et une attention aiguisées, plein de tensions et de contrastes. Un dialogue également entre la présence et l'absence, entre le son et le silence, mais pas vraiment un dialogue qui joue avec l'opposition plein/vide, dans la mesure où le silence est toujours considéré comme une matière musicale, comme une texture sonore à part entière. Quatre pièces parfois difficiles et souvent minimales, réduites à l'extrême, où chaque intention se réduit à une intervention souvent très simple, mais d'autant plus intense et puissante. Recommandé!

Julien Héraud l Improv Sphere l Septembre 2011

La publication simultanée, sous l'excellente étiquette Potlatch, de deux enregistrements associant l'ahurissant percussionniste Seijiro Murayama d'une part à Stéphane Rives (saxophone soprano – Axiom For The Duration) et d'autre part à Jean-Luc Guionnet (saxophone alto), offre bien sûr le plaisir de mesurer, si ce n'est de comparer, les esthétiques à l'œuvre et les traits distinctifs des formations en question – le continu & le discontinu, le frotter & le frapper, le temps & la durée.

C'est pourtant au seul duo (« débarrassé » des Chamy ou Mattin auxquels il est parfois associé à la scène) avec l'altiste que je souhaite m'en tenir ici, car j'attendais tout particulièrement ce disque depuis Le bruit du toit (2007, label Xing Wu) ; si celui-ci avait été saisi dans un temple japonais, la moitié du présent témoignage a été captée à la radio slovène en juin 2010, et l'autre partie très finement gravée par Éric La Casa en décembre cette même année.

La formidable tension qui nimbe les échanges – ou peut-être faudrait-il parler d'interventions, d'interjections – de Guionnet (dans la gorge, dans les dents) et Murayama (par matières primordiales), mieux qu'une crispation, établit les polarités électriques nécessaires à l'érection des pierres (alignées ou en tumulus), à la projection des graviers : cartons perforés, ciel retroué. La raréfaction des gestes sonores ne confère pas à ces derniers la moindre dramatisation solennelle ; simples faits, dans leur hiératisme, leur manière de modestie et leur sobre poésie verticale.

Guillaume Tarche l Le son du Grisli l Septembre 2011

top

of page

|

| |

|

2.gif) |

Reviews

|

|

|

| |

|

Percussionist Seijiro Murayama has traveled a diverse musical path, from sonic onslaughts with Keiji Haino and K.K. Null to his recent spare sonic explorations with Michel Doneda and Lionel Marchetti. His two recent duo releases with like-minded reed-players provide a salient viewof the areas he is now exploring.

French saxophonist Jean-Luc Guionnet needs little introduction, given his work with Hubbub and Ames Room and collaborations with Toshi Nakamura, Eric La Casa, and Dan Warburton. Window Dressing is a study in micro-controlled gestures and timbres: reed pops, sputtered overtones, and pinched harmonics parry with scraped drum heads, hissing brushes, muted snare sizzle, and surgically precise taps and choked rolls. The two use space and silence, building tension and then breaking things with pregnant pauses. Overthe course of a 30-minute piece and three shorter pieces, what could sound stultifying in lesser hands instead develops an enormous sense of purposefulness. The two synch together so closely that the improvisations sound at times almost composed.

Michael Rosenstein l Signal To Noise l October 2012

Place this music somewhere on the sliding scale between older school improvisation and electroacoustic improvisation. Four tracks of about an hour's worth of minimal sound exploration from Guionnet on alto sax and Murayama on percussion, with lots of metallic popping from the horn while all manner of rubbing and scratching sounds issue from the drums, with occasional punctuation from struck membranes. On a previous recording with another saxophonist, Axiom For The Duration with Stéphane Rives, the modus was high frequency/long duration. Here it is most decidedly other, with longish periods of near-silence poked through with splintered rhythms and small notes or short phrases from the sax.

At about the 8-minute mark during the opening track, Procédé, Guionnet lets loose with a long LOUD held note while Muraryama burbles and pangs underneath. After that, things quiet back down for the most part. Murayama is prone to circular rubbings occasionally shot with drum-head snaps, gradually changing the texture from papery to grainy. His sounds are intriguing and well placed, often conjuring up insectile memories, while Guionnet worries a trill or shortens, then lengthens a repeated phrase. Later on in the long first track there is a bit of quick interaction, which gives way to a return to small sounds punctuating silence. When he lets loose with the quick-quick, Guionnet's tone is sharp, a blade chopping notes. His held tones sound almost electronic at times. On Processus Murayama offers wind, fire and water sounds, which move around inside the stereo spectrum.

On headphones or at higher volumes there are some quiet details that may otherwise escape notice: soft movements that may or may not have been deliberate. It makes one wonder whether the title refers to physical objects, or the act of decorating a store window. Or a window itself.

Jeph Jerman l The Squid's Ear l March 2012

Practically unknown except in his adopted country of France – and likely in his native Japan – Seijiro Murayama is a remarkable drummer whose percussion prestidigitation is usually conjured using brushes, sticks, contact microphones, a single snare drum and one cymbal. As these exceptional discs demonstrate, in spite of operating on a microtonal playing field with equal absorption in the qualities of silence and intonation, the results are mesmerizing. More specifically neither CD sounds remotely like the other, although a saxophonist is his partner on each.

Concerned with interdisciplinary links among sound, dance, painting, literature and other arts, Nagasaki-born Murayama initially played in noise-rock bands such as Fushitsusha and A.N.P. Today however his improvisations are often in the company of guitarist Taku Unami, synthesizer player Uta Kawasaki or trombonist Thierry Madiot. A similar autodidact and multi-disciplinarian, Paris-based alto saxophonist Jean-Luc Guionnet composes electronic pieces, plays church organs and is a member of the bands Hubbub and The Ames Room.

Murayama’s rhythmic strategy with Rives is based on multifaceted responses to frequently recurring straight lines. In contrast, while harmony also doesn’t concern Guionnet and Murayama on the one extended and three shorter pieces that make up Window Dressing, the alto saxophonist expels a series of reed variations that throw the percussionist off base. More than half-an-hour of improvising Procédé is the defining track. As the drummer advances the duet with paradiddles and shuffles, the saxophone tone undulates from faint reed buzzing to a kazoo-like bray. In round robin-formation each musician takes sequential turns producing solipsistic tones. More tonally flexible than Rives, Guionnet’s playing encompasses multiphionic harmonies, reed-biting smears and nasal juddering. His tongue slaps are balanced by Murayama’s brushes doing a delicate sand dance on the drum top, with the finale divided between Guionnet’s distant spetrofluctuation plus full force drags, flams and ruffs from the drummer.

Other tracks such as Procession and Procès promote the same mixture of gentle and brutal actions divided among tones ranging from near-silent to stentorian. Along the way Guionnet blows air through his horn without touching the keys, exposes tongue pops and lip-pinched vibrations while Murayama rattles sides and scours the drum top. A final track, Procès balances duck-like cries plus staccato reed peeps from the saxophone with rolling drags and wisps from the drummer. Lastly what sounds like a rubber ball bouncing on drum skin mixed with continuous tongue fluttering from the reedist paradoxically suggest both a conclusion plus a willingness to start all over again.

Unjustly unknown internationally – like too many French improvisers – these CDs should introduce a wider audience to Murayama’s inventive percussion power. Both Axiom for the Duration and Window Dressing are worthy of aural exploration, although Guionnet does have an edge over Rives when it comes to perceptive duetting with the drummer.

Ken Waxman l JazzWord l March 2012

In the sinking daylight, the ringlets of sax seem to spit across the other side of the room as percussion skitters against the wood grains. You begin to find yourself laying prone in the middle of the intractable conversation between rat shit scabble and sudden orange blooms of sunlight. Seijiro Murayama and Jean-Luc Guionnet’s music exists with no prior need. It proceeds without any acknowledgement of its audience. It lacks the aural head-tilts or the showy gesture. In its very lack of recognizable syntax, the music breathes of its own volition. And thank Jesus it’s up to you to figure your own way through it, to chart its choked aloofness. The gulfs of silence that brim between the pockets of their activity are unforced, unhurried -- but rife with a tension. A repeated honk in the dark and a rebuttal of near-inaudible striations -- if it’s not non-existence they’re after then it’s a subtle symbiosis embroidered in obscurity.

I’m hesitant to say that this is music for everyone. This is most certainly not music that functions as an appeal. What it lacks in dynamics, it makes up for in a subtle strain of the wait. Of that long desire that manifests itself in sleepless nights, in your secret implosion in the passenger seat of a moving car.

I mark time with cups of coffee as I listen. I move my hand against the coffee table in long strokes, probing scratches, patches of dulled enamel, crumbs collecting between my ring and finger; Murayama punctuates a rife silence, his percussion charting out space with a stubborn tattoo or a goading slink. Don’t get me wrong, there is no pay off, no climax, no passionate release. You leave the music with hat still in hand. Window dressing? I hear no concealment here; if they’re hiding at all, it’s in plain sight. The hermetic language they drawl becomes so contorted that you find yourself hanging on every misheard word. All flaws seem readily apparent, lingered over, and presented with little accord. It’s an album as bare as this table, as bitter as this cooling coffee, undeniably appealing in its way; although I’m slightly masochistic. I enjoy frustration. I enjoy the work. And this is certainly work.

Tanner Servoss l Tokafi l February 2012

In the 1980s, Seijiro Murayama drummed with Fushitsusha and Absolut Null Punkt. If heaviness was his goal, he started out on the top floor. In the 2000s, he’s chosen a new path, appearing mostly with European improvisers and sound artists like Lionel Marchetti and Eric Cordier. When he toured the US last year with just a snare drum and a few hand-held instruments, Murayama’s objective was to raise the hairs on the back of your neck using the sparest of gestures.

Despite the apparent similarity of their instrumental line-ups, that economy of means and seriousness of purpose are all that unite Window Dressing and Axiom for the Duration. Each is a duet with a French saxophonist, but they sound completely different. For most of the former record, Jean-Luc Guionnet uses his alto saxophone to generate short pops and barely perceptible hums separated by canyons of quiet. Murayama’s playing is just as spare; a beat here, a whoosh of brush against skin there. Every sound he makes feels like a moment of high drama, and when Guionnet finally breaks into a series of arcing high notes and longer exhalations on Procession after 42 minutes have passed, it’s a shattering surprise. Trying to grasp the shape of this stuff is a bit like an advanced class in mindfulness; it’s no small task to hold so much empty space in your head. It might be more rewarding to simply deal with each moment as it comes.

Bill Meyer l Dusted Magazine l November 2011

Jean-Luc Guionnet is one of the most interesting French improvisers alive today, and even if you don’t enjoy his music I find it’s always good to engage with the vague dilemmas he seems to be setting forth in his musical conundrums. On Window Dressing, here he be armed with the alto saxophone and playing against the percussion of Seijiro Murayama, with the cover adorned with photos of a statue which suggests their musical encounter wasn’t far apart from a homo-erotic wrestling match. Unfortunately this record to me feels as cold and static as the marble of that statue. The first long piece (31 minutes) was recorded for the National Radio of Slovenia, and it’s an infuriatingly frustrating instance of musical information being drip-fed to us in vague, hesitant bursts – subsist as best you can on a small puff of saxophone here, a half-completed drum-roll there, in an interminable sequence where almost every spoken utterance is smothered and strangled at birth. Guionnet produces only tiny quantities of sounds that might be deemed musical; most of what we hear is languid breathing effects. Murayama exhibits similar restraint, and delivers himself of desultory paradiddles as though a soldier were holding a gun to his head. Even less musical meat to be gnawed from the bone on the three remaining pieces of extremist minimalist improv, but what’s of interest here is that they asked Éric La Casa (frequent collaborator with Jean-Luc and himself an accomplished composer of no small mien) to record them in a particular way. My French translation isn’t quite up to the task of understanding it, but it seems to me that Eric was using a roving microphone set-up and “digging into the space and tension of the duo”. Sounds like a fairly fluid set-up that allowed him to move around without let or hindrance and thusly capture every nuance of the performances, transforming the implied two-man orgy into a three-way situation that promises plenty of juicy action. Musically, it isn’t quite as exciting as that, but this remains an assured performance of quiet improv which borders on the mystical-mesmerising, documented in sharp detail.

Ed Pinsent l The Sound Projector l November 2011

Guionnet has made something of a habit of skirting categorical boundaries, as likely to engage in pipe organ drones as free jazz extravaganzas as eai as Chamy-ized performance. Here, he and Murayama seek to wring more out of what I hear as the nether reaches of efi, kind of the area you may have expected Butcher and Prevost to explore a decade or so ago, This isn't to cast it as a recherche event; I get the feeling Guionnet is very conscious of this "re-mining" of certain approaches and I choose to listen to it that way, allowing more latitude than I otherwise might, always acknowledging that there may still be lodes hitherto unexposed. Not that I'm often sold on the venture. When Guionnet erupts in plosives, guttural, Mitchell-esque drones or a flurry of squeaks, it's next to impossible not to hear their lineage. On the other hand, the placement of these sounds within the generally gentle framework provided by Murayama (often using brushes or the like) can be quite attractive and thoughtful, setting up a certain tension in this listener's head that alternates between aggravating (in the sense of wondering why they bother) and itchily delicious when, on their own terms, they succeed. Is it too easy to say, "Ah, here's the Evan Parker section."? I don't know, I'm sure Guionnet has other thing on his mind but there no way anyone doesn't register Parker from time to time (or Butcher elsewhere). Murayama as well, though perhaps less overtly, operates out of a similar context; I find his contributions less problematic but maybe I'm over-reaching when I think I pick up references to Butoh at the conclusion of the first 30 minute plus track, isolated strikes sounds that are very moving.

The second track concentrates on rushing air sounds from Guionnet, brushed ones from Murayama, a bit more into early century eai (! :-) ) but with a undertone, to these ears, of free jazz; it's not too hard to imagine Roscoe Mitchell getting to this point. Again, not a deep criticism, just curious about the whys involved. More, harsher airborne rasps in the third then back to a more "traditional" interplay for the final cut, Murayama again peppering the affair with lovely, heavy blows mixed with whooshing scrapes. As before, I hem and haw; it's very well played, well imagined. Had it been on a Butcher solo outing from 2002, I would have been wowed. Should I still be so? Not sure...in any case, listeners without my qualms should find much to enjoy.

Brian Olewnick l Just Outside l October 2011

How is it that two musicians can play their instruments (alto sax and percussion) in a relatively ‘normal’ manner, blowing through the reed, striking a drum, without much in the way of extended technique, and yet still produce a CD that sounds thoroughly original, refreshingly unusual at the same time? Window Dressing, the second duo release by Jean-Luc Guionnet and Seijiro Murayama achieves just this, while also answering many of the questions about where improvisation might go after the end of reductionism at the same time. Big statements to make then, but this is a duo I have enjoyed following a great deal of late, two musicians very much in tune with one another’s thinking, and gradually developing a form of music that hints at so many of things and yet sounds like nothing else I can think of.

The music that spans these four pieces, the first a radio broadcast recording from Slovenia, the last three studio recordings made by Eric La Casa in Paris, is on first hearing sparse, quiet and simplistic. Across the album we hear slow, gradually evolving pieces, tightly defined yet full of silence, mostly made up of small, often repeated sounds from each of the duo, Guionnet moving from soft tones and rasping held notes to little pops and clicks, with Murayama mixing sharp little strikes at a snare drum, rhythmic, often circular textural patterns and repetitive, clockwork, almost click tracks of struck or rubbed percussion. There is a discrete, almost matter-of-factness about the playing, with much of it actually sounding composed rather than improvised (the duo refer to their music together as compositions, though on the occasions I have seen them live there never appears to be anything written down) Often each musician seems to set about making a series of similar sounds irrespective of what the other may, or may not be doing. At times modern, Wandelweiser-esque composition is evoked, with Murayama holding a steady patter of identical drum strikes or Guionnet letting a single note last for a period of time, sounding as if they are not reacting to one another, but merely placing sounds into specified time slots, but this isn’t the case, and this music is improvised, just in an unusual, simple and yet somehow right-angled manner. There is no sense of call-and-response and no feeling of urgency, with the simply played sounds just placed and left with seemingly great confidence- the two musicians having played together very often for many months having lived together in the same apartment for a period of time. The music they have gradually developed together seems to reference the American composition of Feldman, Brown, Tenney, but also the to-and-’fro of eighties and early nineties European improv, but all slowed right down and with extended, tense space inserted between events and the occasional surprise, such as the strong, searing sax lines that Guionnet lets fly with every so often.

This is clearly very thoughtful music indeed, a kind of study of the spaces between sounds as much as it is about the sounds themselves. Perhaps a cliché, but I am reminded of classical Japanese calligraphy, beautifully crafted, clearly picked out black characters placed beside each other against a white canvas, the beauty of the text to someone that cannot read the letterforms coming from the way the intricate, yet confidently picked out characters create white shapes between them, the neatly brushed letters spaced evenly apart but with new intricate forms appearing in the spaces between them. Although the sensation is always of quiet and calmness, in places the sounds are actually quite loud, particularly coming from Guionnet here and there, so reductionism is in place as sounds are held back and white space is given a key role, but the actually sounds themselves portray a real musicality and sensuality- Guionnet and Murayama paint in broad strokes rather than tiny scratches but still nothing is wasted here and sounds only appear when they need to. Window Dressing is an intense listen then, often an exercise in listener stamina as the patterns of this music sit continually in position, never hurrying, never about to explode into instrumental pyrotechnics, but exuding a simple, almost hypnotic beauty and a remarkable use of space quite unlike anything present in much else of what makes it onto CD these days. Lovely stuff all round, released on Potlatch.

Richard Pinnell l The Watchful Ear l September 2011

Back in 2007 Potlatch released Propagations by Marc Baron, Bertrand Denzler, Jean-Luc Guionnet and Stéphane Rives, a saxophone quartet unlike any other, and subsequent releases on the label have focused on individual explorations by the members of the quartet. These two new outings, following hot on the heels of Tenor by Denzler, continue that trend, and mark the Potlatch debut of Paris-based Japanese percussionist Seijiro Murayama.

Guionnet and Murayama have collaborated regularly since their duo album Le Bruit du Toit (Xing-Wu) in 2007. Window Dressing consists of four tracks, the longest recorded live in Ljubljana in June 2010 and the others in Paris in December 2010. Murayama is an economical percussionist, favouring a spectrum of subtle, delicate scraping and rubbing sounds which act as coloration without being the focus of attention. He employs an extensive and well-calibrated range of techniques in response to Guionnet's sustained notes and truncated staccatos. The Ljubljana track, Procédé, at 31 minutes, allows both players scope to display their full repertoire. When the saxophonist unleashes a sustained clarion blast with a harsh edge, Murayama responds with a series of rolls which only fade away when the Guionnet moves down a gear. His sustained notes attract scrapings of various surfaces interspersed with occasional snare hits. In contrast, on the shortest track, Processus, both players are restrained throughout, the saxophone's swelling tones and the sound of breath through tubes totally compatible with Murayama's white-noise friction. One wonders whether the album cover, a photograph by Guionnet of a sculpture of two bodies seemingly locked in combat is appropriate to such agreeable music.

John Eyles l Paris Transatlantic l September 2011

These recordings by the duo of Guionnet on alto sax and Murayama on percussion, made at Radio Slovenija and in Paris in 2010, offer no-frills Noise and sound art, focusing on duration, not rhythm, textures rather than tones. Nearly half of the31 minute Procédé is silences, while much of the rest is stentorian blasts on saxophone. Processus is a masterly synthesis of gravelly percussion and toneless sax sounds. Performing, and listening to, such gruelling, rather inhuman material requires commitment. I'm reminded of the consultant's reply, years ago, when I'd asked if having a barium enema was unpleasant. "Well, I wouldn't do it for a hobby."

Andy Hamilton l Wire l October 2011

Two new releases on Potlatch, a French shelter for improvisation, and both of them include Seijiro Murayama on percussion, twice in duet with a saxophone: the soprano of Stéphane Rives and alto of Jean-Luc Guionnet. That is about the only two things that are similar here on these two discs.

However, 'extreme' is a word that can easily be applied here, but then one from a totally different perspective. If the other one is 'loud', then this one is 'quiet' - here sparseness is what it is all about. I could almost talk about this in the very same words: "This is - literally - very strong music, an endurance test, for the players no doubt, but also for the listener. Clocking at fifty-some minutes, this is CD can't be played without full attention." Except there is a no continuity in the music, but rather many loose, fragmented sounds, and sometimes making sustaining events, but then these appear to be rather 'soft'. I must admit that playing both CDs in a row is quite a lot to ask for, while each album individual has a great quality by itself - and its tempting to play both at the same time and create a multi-mix out of them together.

Frans de Waard l Vital Weekly l August 2011

top

of page

|

| |

|

|

|