2.gif) |

texte

de pochette |

|

|

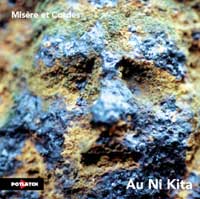

| Politique

de la guitare !

Il

s’agit bien de cela : l’organisation pour un temps donné

de la vie publique d’une cité de vingt-quatre cordes.

Ensemble,

Pascal Battus, Emmanuel Petit, Dominique Répécaud

et Camel Zekri balisent un dédale sonique dont nul ne connaît

le plan, pas plus que les limites. Il conviendrait d’imaginer

une termitière dont on parcourt simultanément les

moindres détails, emporté par une multitude de sons

en perpétuel mouvement. Les guitares – il y en a ici

deux acoustiques (l’une étant prolongée par de

l’électronique) et deux électriques (une Fender

Stratocaster et une Gibson “environnée”) –

sont des instruments essentiellement percussifs. À sons courts.

On est parfois tenté alors de faire beaucoup de sons courts,

pour combler l’espace, et l’on réussit seulement

à combler l’espace d’ennui. La guitare contemporaine

contourne cette contrainte à l’aide de moyens divers,

archet volé aux violonistes ou e-bow, ventilateur ou raclement

de tige métallique, et l’on peut ajouter à la

liste le larsen, bien évidemment. Ainsi, un tel quatuor dispose

d’un arsenal assez terrifiant de modes d’attaque et d’entretien

du son, sans oublier un éventail de timbres que certains

qualifieront de luxuriants. On a là en fait un “instrument”

que l’on peut comparer dans son fonctionnement à un

gros synthétiseur modulaire à 24 oscillateurs, avec

la vitesse de réaction en plus. La musique est un voyage

à l’intérieur même de cette mer de micro-événements

en perpétuel tuilage, où l’on est porté

très sûrement par des ondes plus amples. LaMonte Young

disait qu’il est plus facile d’entrer dans les sons quand

ils sont longs (1). Ici, on

a le meilleur des deux mondes, le crépitement des étoiles

et l’étendue du désert.

Cette

musique, produit de la rencontre formelle (c’est un vrai groupe,

pas une rencontre-de-festival, même si ces dernières

sont parfois réussies…) de quatre représentants

de tribus pratiquant le cousinage, dessine en temps réel

la carte du paysage foisonnant qu’elle défriche. Comme

chez Borges, cette carte recouvre l’ensemble du territoire.

À l’inverse, l’histoire est nettement moins triste.

En sept chapitres et autant d’incursions dans la musique pour

guitares, pas un seul lambeau n’est laissé sur le côté.

La bête fait feu de tout bois, se nourrit de souffles brûlants

et de velours pincés, de stridences qu’on jurerait numériques,

et même d’un chant de transe qui envoie valser le couvercle

au-delà des nuages et entraîne le groupe aux confins

de la sauvagerie.

Laurent

Dailleau

P.

S. (de l’usage des étiquettes…)

La musique gravée ici me semble relever d’une catégorie

qui existe déjà ou qui reste à inventer, le

hörspiel muet. Car la qualifier de musique-contemporaine-pour-guitare

serait loyal mais peut-être mal compris par certains. De même

pour musique-du-monde, tout aussi objectif et qui serait, lui, mal

compris, mais par d’autres. Musique-improvisée, compris

par tous (quoique…), mais prévisible. Musique-du-vingtième-siècle

: probablement vrai (voir dates d’enregistrement), mais tellement

daté. Finalement, politique-de-la-guitare ne serait pas mal

du tout, mais pose un problème crucial : que ranger à

côté de ce disque, dans le même bac ? Débats

interminables, jalousies, chantages divers…

Non, la vie n’est pas une montagne de sucreries (2)…

(1)

LaMonte Young disait aussi : “un jour j’ai essayé

beaucoup de moutarde sur un navet cru. J’ai aimé ça

plus que tout ce que j’avais jamais entendu de Beethoven.”

(2) Life is no candy mountain.

Candy Mountain est un film de Robert Frank dans lequel il

est surtout question de… guitares.

|

2.gif) |

liner

notes |

|

|

| conceptualist

position

overt imagery

declared significance

proscribed

referential

interruption

narrative

negation

identity

difficulty

form

emblematic

strategy

displacement

absolute

formal gestures

installation

conundrum

slack

incompetence

iconography

iconographic

open signification

perceived

complicity

unconvincing

deny

nihilism

accommodate new

accessible

embrace images

contradiction

automatically

formal

formally expert

argued

simulationist

unpopularity

intensify

independence

theoretically difficult

effortlessly

obscure

authorial uniqueness

recognition

unformulated

resolution

fantasy

speculative thought

vital

stringency

entertainment

accurate justifications

depleted

requirements

repetition

exchanges

stimulation

relationships

endlessly revised

assimilation

self-purification

despairing

contrasted continuum

affirmative

specialised

transgressive

varieties

plucked sound

instrument can be taken to a particular level of development. Further

modifications actually become counter-productive

expressiveness and performance

inventive eccentricity

excess

decoration

layers

actual sound

tone-colour associations

central traditions

isolation and detachment

authenticity

1840

undergrowth of musical life

guitar's allure

quickly absorbed

17.835

metamorphosed our aural perception

imagination

self-exploration

analytic evaluation

nostalgia

Keith

Rowe

|

2.gif) |

chroniques |

|

|

Quatre

guitares, deux acoustiques (Emmanuel Petit, Camel Zekri) et deux

électriques (Pascal Battus, Dominique Répécaud).

Dans ce labyrinthe de textures chimériques où les

instruments (empruntant à cet égard la voie tracée

par l’iconoclaste Keith Rowe) sont davantage conçus

comme des sources sonores en perpétuel mouvement, chacun

des guitaristes de l’industrieux quatuor Misères et

Cordes conserve sa voix propre dans la (dé)construction du

son collectif où fourmille tout un enchevêtrement de

bourdonnements, raclements, vrombissements, frottements, grésillements

et autres mystérieux cliquetis. Sorte de fascinant rituel

tribal, aux modes de jeu à mi-chemin entre des passages paisibles

(presque minimalistes) et d’exubérants chambardements

cacophoniques.

Gérard Rouy

l Jazz Magazine l

Novembre 2006

Au

Ni Kita, autre alizé auquel viennent nous convier Pascal

Battus, Emmanuel Petit, Dominique Répécaud et Camel

Zekri. Ce qui m'intéresse, en improvisation, ce sont ces

musiciens qui prennent le risque de frôler le désastre,

qui parfois en cherchant avec patience et acharnement, ne trouvent

pas, séjournent dans un temps musical, temps qui pourtant

promet tous les stimuli de l'exaltant et débouche quelques

secondes, minutes plus tard sur le merveilleux (au sens de ce que

pouvait ressentir un contemporain de Jérôme Bosch devant

une de ses toiles, à savoir, terreur et émerveillement

de l'enfance). En un mot, des musiciens dont le son est en permanent

devenir. Nos quatre guitaristes sont de ceux-là, toujours

en équilibre instable, fragile et puissant à la fois.

Leurs cordes vibrent, sympathiques, mais distinctes, d'une idée

de guitare à l'autre (comme dirait Keith Rowe). Il y a partage

du travail, grain à grain, strate à strate dans l'espace

qui se dessine – aussi – en profondeur, en une démocratie

qu'aucun gouvernement ne dirige, où chacun fait signe et

non signature. Un vent souffle, venu du fond des caisses, du cœur

des membranes d'ampli, portant des effluves, des couleurs de cordes

: acides, corpulentes, distordues, rappeuses, grappillées,

"clusterisées", caverneuses, craquelées,

grésillantes, abyssales, fulgurantes, pétaradantes,

sèches, rondouillardes, STOP ! - REWIND !

Patrick

Bœuf

l Peace

Warriors l Mars

2002

|

2.gif) |

reviews |

|

|

Step

right up folks: four guitars, all improvising, and no waiting.

That could easily be the come on for this remarkable 63-minute

session of collective, non-idiomatic string inspiration. Non-idiomatic

is also an understatement, since the members of Au Ni Kita - which

means guitar music in the language of the Solomon Islands - offer

maximum variety in their sounds since each comes from a different

guitar background.

Pascal Battus is a full-fledged experimenter, concentrating on

what he calls surrounded guitar, that is one that's extended with

such objects as small engines, amplified percussion, the e-bow,

radio and electronics. Acoustic guitarist Emmanuel Petit moves

between jazz and new music and has worked with the likes of percussionist

Lê Quan Ninh and saxophonist Michel Doneda. An early post-rocker,

Dominique Répécaud is known for his membership in

the band Soixante Etages. Finally, so-called ethnic music is represented

by Camel Zekri. Of Algerian-French descent, he has played not

only with sonic explorers like Ninh, Doneda and electroacoustian

Xavier Charles, but also with traditional performers from Africa

and Europe as well.

No hootenanny or cutting contest, the work of the four instead

melds into one 24-string instrument. They complement one another

so well that it's almost impossible to tell who plays what and,

as a matter of fact, where one instant composition ends and the

next begins.

Imagine

the audience at the festival site in Vandœuvre-lès-Nancy,

France where the disc was recorded, as participating in a futuristic

tribal ritual. As one man creates his version of sound, the others

try to amplify it as best they can, not by adopting his style,

but by expressing the parts of their own that will fit.

Which

means that at one point you'll hear a solo acoustic guitar interlude,

accompanied by the bang, crash and chalk-on-the-blackboard sounds

that probably come from electronics. Other times, as on "Eg

Sumo" a heavily amplified rock style complete with fuzz

tone licks - from Répécaud, perhaps - succeed steady

strumming that dissolves into what could be an approximation of

a jet plane landing or giganticrubber bans being stretched.

Like

German Hans Tammen, a practitioner of "endangered guitar";

Battus appears to spend most of "Thinging"

battering his poor instrument into submission. Sounds that could

be a lathe turning, a bowling ball rolling down the stage or a

fan belt slapping against the mechanism make their appearance.

Earlier, what appears to be the rumble of a motor, and a duet

between what appears to be one musician sawing on metal and another

vocally practicing his opera scales, can't really be ascribed

to any one player.

If

the fire bell ringing comes from Zekri, is it he or Petit who

supplies the acoustic guitar interludes? And is the tiny, flamenco

dance of movement with dampened strings on "Argil"

a traditional or extended technique? These are questions you'd

like to ask, but are satisfied not to, since the CD is satisfying

without interpretation.

Although

there are times that you feel that a background in auto mechanics

or metallurgy would be more appropriate than musicology for judging

the results here, the overall impression is fascination with what

the four create.

Other

European, such as Tammen, Derek Bailey and Keith Rowe are in the

midst of creating a new identity for the guitar, divorced from

its pre-20th century associations. The four plectrum pioneers

here can be added to that group.

However,

it's odd that they've taken a pun on mercy (miséricorde)

for the title of this disc. For the cordes (cords, chords) are

only intermittently in misery (misère). A more appropriate

name for the session is suggested by Rowe in the booklet notes:

"inventive eccentricity".

Ken

Waxman l Jazzweekly

Though the saxophone quartet has found its place in the world

of improvised music, the guitar quartet is still a rarity. Along

with Fred Frith's guitar quartet and André Duchesne's Les

4 Guitaristes de l'Apocalypso Bar, the French group Misère

et Cordes might just have a lock on the market. But unlike the

other two units, these four operate firmly in the world of open

form, spontaneous improvisation. What could be a frightening skronkfest

in the wrong hands turns instead into a series of improvisations

that combine timbral explorations of craggy textures with collective

counterpoint. One of the things that makes these improvisations

work is the variegated approach of each of the participants. Pascal

Battus uses his "surrounded guitar" as an electronic sound source,

building percussive agitation out of shattered chords, feedback,

and static. Emmanuel Petit's acoustic guitar adds steel-sharp

needlepoint and resonant brittle chords reminiscent of Derek Bailey.

Electric guitarist Dominique Répécaud draws on a

rock vocabulary, tossing fuzzed and trayed fines into the mix

with an economical sense of space. Camel Zekri uses the clean

ringing tone of classical guitar along with an African sensibility

of flowing percussive patterns to add a linear flow to the improvisa-tions.

The free orchestrations range from pointillistic conversations

to bristling sheets of clanging electronics and chiming overtones.

There are moments when their exuberance tends to throw the balance

from densely packed abstractions toward frenetic turmoil. But

through most of the release, careful listening and an open, spacious

sense of improvisational development guide these four through

a formidable set of sonic inquiry.

Michael

Rosenstein

l

Coda

l

March/April 2002

One would imagine that a performance of four guitarists

would be a rockish affair, but Battus, Petit, Répécaud,

and Zekri on Au Ni Kita turn the occasion into a challenging

opportunity for creative expression. The sound arising from the

four musicians is quite distinctive. Petit plays the acoustic

guilar, Répécaud the electric version, Zekri a classical

guitar augmented by electronics, and Battus uses a surrounded

guitar. This results in having pockets of differing tonality continually

bursting onto the scene. The music is not devoid of flow, but

it is dominated by broken, serrated lines and a recurring use

of space as a partner to the sporadic sound. Petit and Battus

hold forth at opposite ends, placing the electricity of Répécaud

and the electronics of Zekri in the center. This pattern results

in an arc of inundating waves of sound.

The music is often presented through the uniting of two guitarists

who probe the other's thought patterns by sending out feelers

of choppy notes. When a response is received, open conversation

emerges and the rest of the players join in to build the selections

into robust symphonies of cacophonous strings. Battus scrapes

his strings, Petit uses percussive thumps, Répécaud

elongates the sound waves, and Zekri magnifies his notes through

electronics in the total abandonment of reserve. Thinging

is indicative of this massive eruption that disturbs the prevailing

calm. Although compositional credit is given to each of the seven

selections, all songs produce the impression of being instantly

and collectively composed. The music combines emotionalism with

intellectualism; while it is not grasped without effort, it is

worthy of concentrated attention.

Frank Rubolino

l

Cadence

l

December

2001

ln

the language of the Solomon Islands, it seems, Au Ni Kita

means music for guitars; and this is indeed music for guitars.

Four of them - two electric (played by Pascal Battus and Dominique

Répécaud), two acoustic (Emmanuel Petit and Camel

Zekri). The players keep each voice distinct rather than creating

a homogenised ensemble sound. Approaches vary according to the

styles of the individual players, but generally the guitar is

viewed as a sound-generating machine rather than a mere instrument.

No tunes, then, but an intriguing mesh of clicks, buzzes, scrapes

and other elements from the extended vocabulary.

Julian Cowley

l

Wire

l

August 2001

Conditionally free improvisation has gestures and flow systems

that is, at times, predictable and limiting. Often noisy sessions

based on blowing and energy have obstructions that can lead to

impatience. Misère et Cordes is neither overly boisterous

nor overtly zealous. The musicians open your ears (and mind) to

a fresh experience.

This guitar quartet record combines all aspects of a guitar sound,

save energy thrashing. It approaches improvised sound from an

almost minimal philosophy, defaulting to a less is more attitude.

The combination of instruments allows for a variation of thoughts,

such as a fuzzy electric onslaught, countered by some freeform

classical guitar.

Rarely do all four musicians have at it at once, except on Analog,

a fifteen plus minute track, where a series of tension filled

passages are processed electronically. One might even go so far

as to say the track rocks out with a thumping progression and

a bit of wordless vocals.

But mostly Au Ni Kita comes from a European free tradition

of finding sounds, working and reworking them for listeners to

consider or more importantly for the other members of the quartet

to consider. Restful passages are countered with pops, clicks,

and electronic hum. It goes without saying that the deconstruction

of music performed by this quartet has a definate flow effect.

Although randomness is present, it neither limits nor distracts

from the sound construction.

Mark Corroto

l

All

About Jazz

l

July

20001

|

|

|

|